All Points Bulletin

EPISODE 1:

ISTANBUL (THE17)

Bill Drummond suggested that I write some words to accompany the performance of The17 that I am coordinating for him in Istanbul.

Only, I’ve tried writing a few words and that was too difficult as there is too much tied up in the performance for me to summarise easily, and besides, there’s too much I want to say about the experience, and my relationship with music (recorded or otherwise). So, if you’re not interested in that, then just skip to part two.

1. Listen

Like many men of my age I have obsessively collected music since I was a teenager, when the accumulation of vinyl was as close as I could get to the pages of the NME and lives far more exciting and emotionally charged than anything that I could imagine.

Every pound I earned from part-time jobs went straight behind the counter of Movement or Pink Pig Records on studiously contemplated purchases that were whisked home to be played repeatedly with reverence, or occasionally disappointment, before taking its place amongst the others on my shelf. But as I accumulated a record collection I also attempted to accumulate an identity that I could wear at school, trading cassette copies of my prized purchases for the acceptance and coolness I desired but that evaded me. But it didn’t matter, because I had the records and I could play them whenever I wanted, and taste a slice of life, love, loss and passion that I couldn’t hope to find in my small village.

As time passed, and we slowly gained access to our parents’ cars, we would start going to see almost any band we could that had stumbled into our radius of dingy venues in Oxford, Aylesbury, Northampton or Coventry. These euphoric evenings provided a shared release of a kind that was only just becoming conceivable to us. The graduation from recorded to live performance was exciting as the graduation from pornography to intercourse, and equally beset with triumph, frustration and disappointment. Those black discs in my room were perfectly defined and infinitely repeatable; but the live experience was something altogether more interesting.

My records constituted the bulk of my possessions when I left home for university. They also constituted the bulk of my identity and granted me access to friendships with a reassuringly similar set of teenage boys with overlapping record collections and equally insatiable appetites to soak up all the music that the the city could offer us. We went to gig after gig, wore the t-shirts, stole the set lists and, of course, we bought the records.

Then one Saturday night, at the suggestion of a girl who I had previously traded Lou Reed albums with, I went to a dark warehouse and my relationship with music changed forever again. Along with indie kids across the country I swapped guitar riffs for repetitive beats and synthesised bleeps, and bedsit melancholy for uplifting vocals. I swapped records that aimed to capture a band’s musical prowess for records that didn’t care about musicianship or live performance, and that only wanted to be blended seamlessly into others. Music that was intended as a communal experience, not as homage to a band of egos – DJs were our friends, tunes were our anthems and love was the message.

I stopped going to gigs almost overnight and realised that I needed to start again with my record collection. I bought a pair of Technics SL-1210s and tried to track down whatever tunes from the weekend that I could still recall on a Monday afternoon in the record shop. But by Monday evening in my bedroom even those records I had been able to find sounded different. The stimulation and stimulants of a crowded warehouse had somehow gotten into the grooves and made the music more than the record.

These new records also had an inherent scarcity: limited pressings, imports, bootlegs and remixes meant that a DJ was defined by what records where in his bag, but not for long. The arrival of CD decks and CD-Rs changed the game again. I had been copying music via cassette since school days, but suddenly being able to quickly make perfect copies of whole albums was a paradoxical thrill for an obsessive collector – I could suddenly own a copy of almost anything I wanted, but these copies felt like cheap imposters amongst the rest of my collection. Yes, the cover art was missing, but had they lost something else too?

By the time mp3s, downloads and iPods arrived I had fully surrendered to convenience. I ripped my CDs and much of my vinyl to mp3s that became indistinguishable from the gigabytes of illegal music they nestled amongst. I now carry around an iPod with over 40 days of music on it, much of which I only heard once before it got buried away amongst every other track it is competing with. Alongside mixes, podcasts, singles, albums, remixes and re-edits I have more musical choice, convenience and immediacy than ever, and yet (or because of this) navigating the list of titles with the scroll wheel to find the record (if I can still use that word) to play is harder than ever. When I listen to it from a computer or through my headphones it is too frequently a solo activity, and I have to fight the temptation to skip and jump between tracks. Something is missing, or had become lost along the way.

And yet if it wasn’t for this technology I would have very little music in my life at the moment. I am living thousands of miles from my boxes of CDs and records, and yet I am constantly listening to and discovering new music from a variety of blogs, online record stores, forums/communities and internet radio stations.

But at least I still have the ‘records’ or at least the files. True, I suspect my son won’t have as many dilemmas about deleting my iTunes library as he would about chucking my records and CDs in a skip when I die, but I still possess the music. But not for long. Increasingly our music collections are becoming no more than Spotify playlists, Youtube favourites, or Soundcloud ‘likes’ – just a click and a link away (as long as you have an internet connection), but unlikely to be bequeathed. Our relationship to music is becoming more personal, more insular. As we click and share with our Facebook friends our communal experience is becoming dispersed and fractured. In their own time they may listen, skip or comment, but we don’t share the experience.

But is it fair to blame the decreasing impact of music on me on the medium, rather than myself? After all, I rarely go to gigs or clubs these days and I enjoy them less when I do. Conversely, I listen to, and sometime play, records on an internet radio station and enjoy sharing music and more with a community of like-minded friends (many of whom I’ve never met). Isn’t this just another change in medium, like the gramophone before it, which the older generation always lament but from which music somehow always thrives, or at least survives? After all, aspiring bedroom producers and DJs everywhere now have studios in the laptops and can distribute their music more easily than ever, so shouldn’t this help good music come to the fore?

But all this activity is creating a lot of noise that is becoming increasingly difficult for me to filter out. Each new record (or replayed old record) is now competing with 23 years of other musical memories within my 40 year old brain, rather than occupying the prime positions in my 17 year old brain. All new experiences in life create excitement, and all repetition creates boredom. A new city is exciting at first, but even the exotic becomes mundane after a while, and it is only shared personal experiences that can cut through it.

Which is a long way of explaining why I am so keen to bring The17 to Istanbul – to see if we can create a unique piece of music that only we will hear only once, and in the process to create some kind of connection with a group of people that will last for longer than I am here. In doing so l hope to demonstrate that the magical “something” that music can arouse is indeed greater than the sum of its frequencies (recorded or otherwise).

2. Record

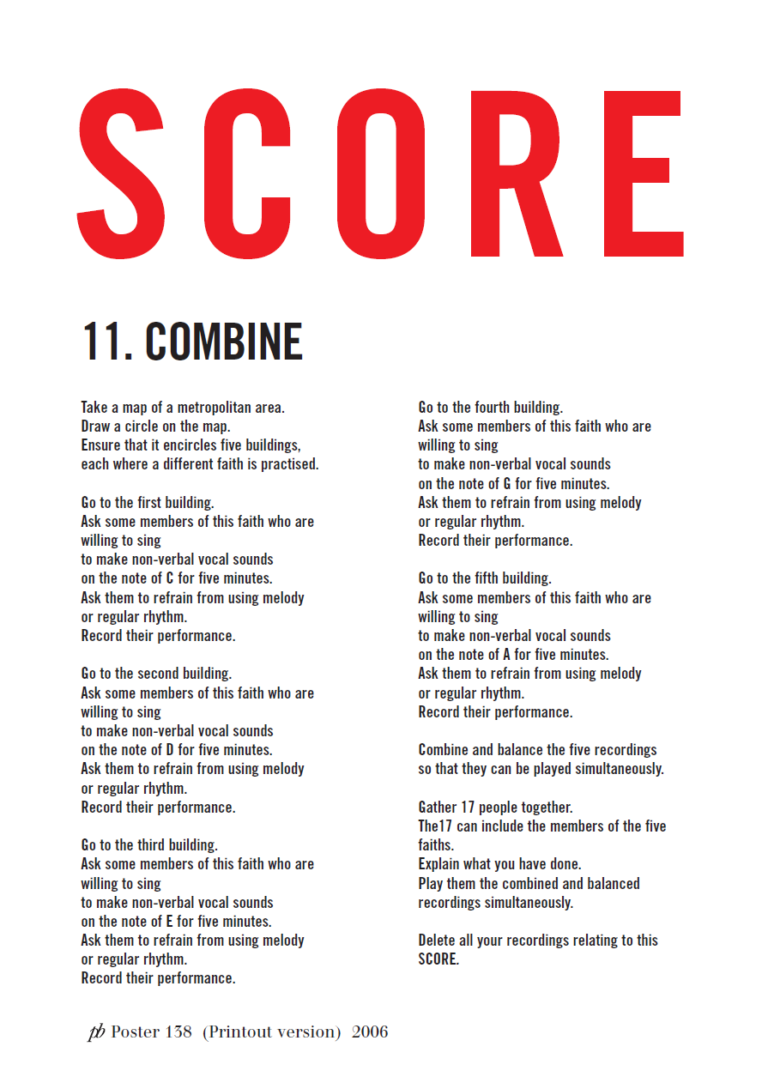

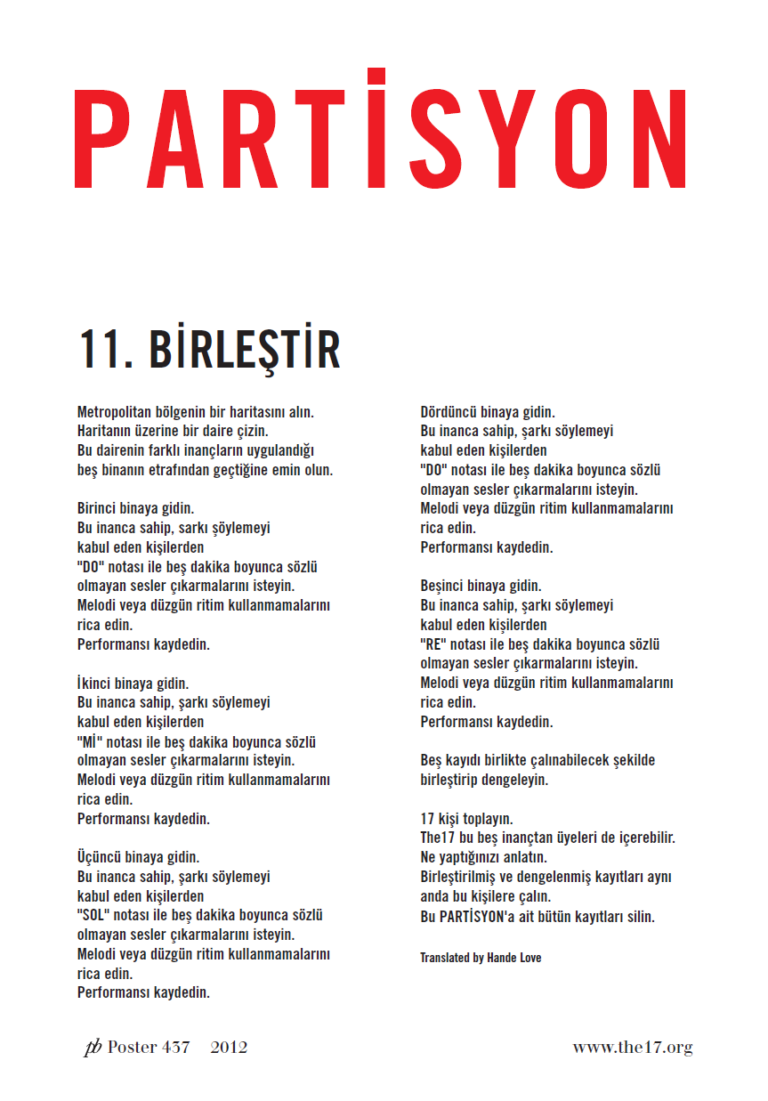

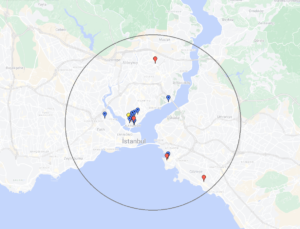

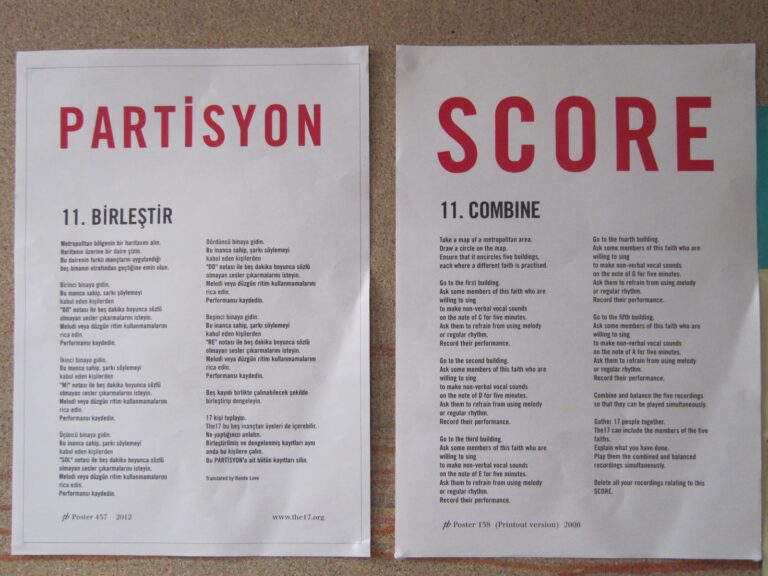

In a city where the iPod is still an aspirational item, and most people seem to possess an array of musical talents, my attempts to describe The17 are usually met with polite, yet slightly bewildered responses. Yet I have had to try to do exactly this dozens of times to friends, family and strangers, (sometimes in English but just as often in my faltering Turkish) in order to try to recruit and record choir members of five different faiths for the Istanbul performance of “Combine”.

Back in London, where the twinned performance of “Combine” will take place, nearly every commuter has a pair of headphones from which they build a small wall of sound to enclose some personal space. Here it is still (for now) somewhat different. On the streets, buses, trams and trains people still talk to each other, and feel free to play with children and give them sweets without asking permission (something that is almost unthinkable in London), and it is this genuine hospitality and friendliness that I will need to draw upon, particularly as any multi-faith project here is laden with tension, and is liable to be viewed suspiciously.

It wasn’t always this way. As a key trading point for millennia Byzantium, Constantinople and then Istanbul has always needed to welcome a wide range of faiths and cultures. In Ottoman times Jews and Christians accounted for about 40% of the city’s population, but following a steady exodus (voluntarily or otherwise), of Greeks, Armenians, Jews and Slavs, and a swelling of the city’s population from internal migrants, today non-Muslims account for less than 1% of Istanbul’s 17 million inhabitants, and their communities are generally quite discrete. Amongst the Muslims too there are heightened tensions between the majority Sunni and minority Alevi, with the effects from recent attacks in the south-east felt across the country.

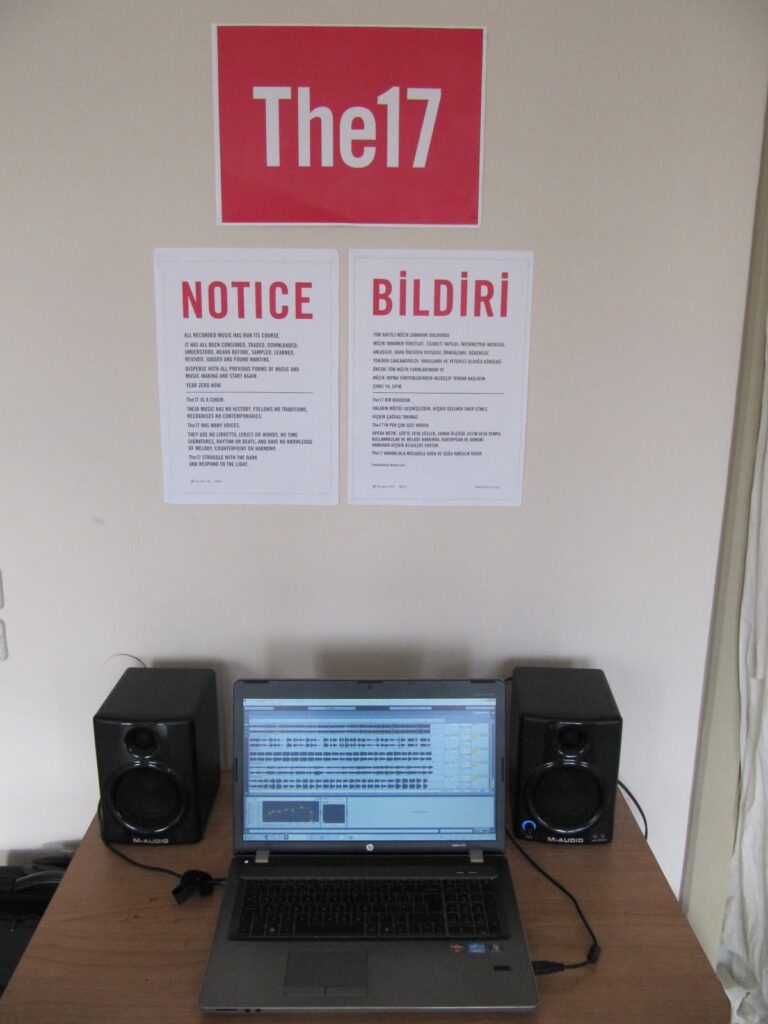

Consequently, in attempting to recruit members of five faiths for “Combine” I find it necessary to stress that other scores written for The17 have included groups of different ages, groups from schools, factories, homeless people and taxi drivers, and that this score just happens to be based around faith. Unsurprisingly, explaining why “Recorded music has run its course”, why the recordings must be deleted afterwards, and where the association with graffiti comes from does very little to help.

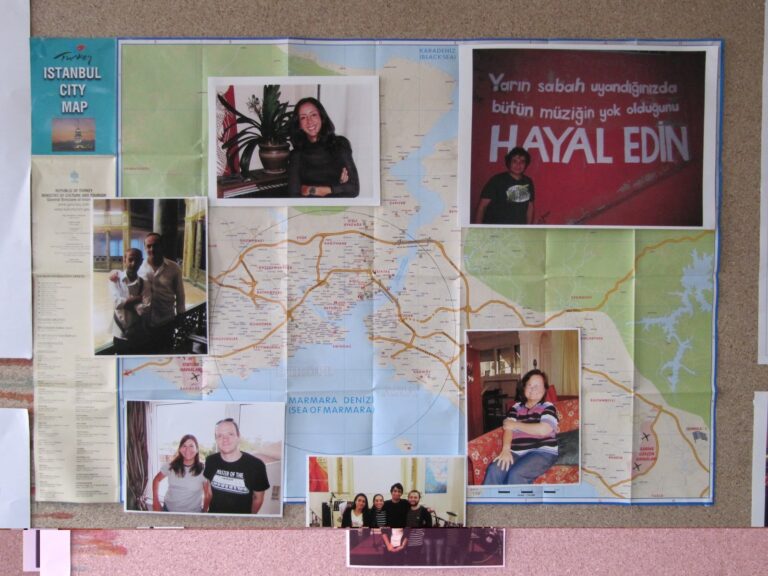

Fortunately I have help and support from my wife, Hande, and two Turkish artist friends (Alp Yavuz and Hülya Küpçüoğlu) who embrace the project’s challenges and possibilities. Fortunate indeed, as my limited Turkish, and even more limited network of connections make it practically impossible for me to recruit five faiths alone, or to paint the “Imagine” graffiti.

It starts promisingly enough. Phone calls are made, and emails sent by Hande, Alp and Hülya to Jewish, Catholic and Orthodox friends, and a handful of politely interested responses received. But as these are pursued people become increasingly wary, or do not respond at all. Some “maybes” turn to “no”, and even people who initially offered to put us in contact with others of their faith dry up. We contact other friends, and friends of friends, but just as many of the religious communities here live in their own bubbles, so too do most of our mostly liberal secular friends, and we soon run out of contacts.

A Jewish friend, Jessica, contacts the Chief Rabbinate, and puts us in touch with a Rabbi who he thinks may be sympathetic. He seems keen to help, but not until after the holidays of Rosh Hashana and Yom Kippur, and he asks us to send a written request which is then politely ignored. An Orthodox friend goes on an extended holiday and the few Alevis contacts we have are all predictably reluctant. With only one Sunni confirmed, and only a few weeks before the Bayram holiday, after which we will be leaving Istanbul for good, the apparent simplicity of the words of the score feel in stark contrast to the scale of the task ahead. At least the score only requires five faiths, and five minutes, one of Stockhausen’s scores featured a string quartet in separate helicopters above a city and a dancing camel. (Having since read a few more of The17’s scores, I am equally glad I wasn’t asked to perform Score 9).

Meanwhile, Hande has translated the “Combine” score, along with “Imagine” and the “All recorded music” notice, and they have been beautifully formatted and published on The17 website, along with a news article announcing the performance. So, no pressure then. Bill remains supportive and encouraging, but I can see little cause for optimism. I hope his arrangements for the Hackney performance are coming along more smoothly.

It was a “do it yourself” attitude that somewhat uncharacteristically led to me taking on this performance and I realise that it is going to have to be the same attitude gets it done, so I decide to take matters into my own hands. Armed with the translations, my microphone and my rudimentary Turkish I decide to take the words of the score at face value – to identify buildings where different faiths are practiced and “Go to the first building. Ask some members of this faith who are willing to sing to make non-verbal vocal sounds on the note of C for five minutes.” I hope that the Turkish custom of providing hospitality to helpless strangers is still alive, and that I will have more luck in person that we have had to date with phone and email.

Either way, I will have tried, and will have some new encounters and experiences during my last few weeks here. It seems to me that The17 is more about the shared experience of creating music than the music itself, and so I hope optimistically that this project can become a success even if it fails. As Bill says, “Whatever the results are they will be a hundred times better than not doing it.”

The first place on my list was the fortress-like Neve Shalom (Oasis of Peace) which is Istanbul’s primary synagogue. Despite its name, it has been attacked by terrorists three times in the past twenty five years, and so security is understandably tight. The only person I could speak to was a bulging security guard who told me to come back after 1pm. When I did a different, but equally bulging, security guard said they wouldn’t let me see anyone without first requesting an appointment via the internet, which is exactly what we had already done more than ten days previously without a response.

Not a great start.

My next stop was the beautiful Roman Catholic Church of Santa Maria Draperis. Despite being on Istanbul’s busiest shopping street the Church was utterly deserted, although at least it was open. In the quiet sanctuary inside I wandered in the silence amongst the many icons and relics in the hope that a priest or some worshippers would show up that I could accost, but no one appeared. Even the running hosepipe in the garden led to no one when I followed it. So, a total blank again.

Further up Istiklal Caddesi was the imposing Roman Catholic Church of St Anthony of Padua, where I was able to speak to the man running the bookshop – he took pity, or interest, in my request and took me next door to whatever the Catholic version of a manse is, where I spoke to a young clerical assistant who thankfully spoke English. My explanation of the idea behind The17 was met with the familiar polite, yet bemused response. Notwithstanding, when he read the score he became keen to help, and said he would approach some members of the congregation who he thought might be interested to be involved, but he obviously couldn’t promise anything, and would email me if he was successful.

Then onto the impressive Greek Orthodox Church Aya Triada, which was closed, securely locked and deserted. But after wandering around the adjoining ecclesiastic offices I eventually met a Greek lady who spoke perfect English and was interested in the project. She said I was welcome to come back at 5pm when there was a service, but as there are fewer than 3,000 Greeks in Istanbul they often only get three or four people at their weekday services, and so I shouldn’t get my hopes up. So I did what I should have done at St Anthony’s and asked her to participate herself. After some consideration, and persuasion, she agreed, provided a friend of hers would do it too. She took my details and promised to contact me within the next couple of days.

I then tried a French Catholic church that was also closed, before taking a long and painfully slow taxi ride to Ortaköy to the Etz-Ahayim Synagogue. The large metal gates were locked, but a buzzer at the side was eventually answered and my polite query met with a brusque “Kimse yok” (“No one here”). Etz-Ahayim means “Tree of Life”, but not today apparently.

So, after a very long and hot day I had secured two half promises, but no recordings, and had exhausted my a-list of buildings, and exhausted myself.

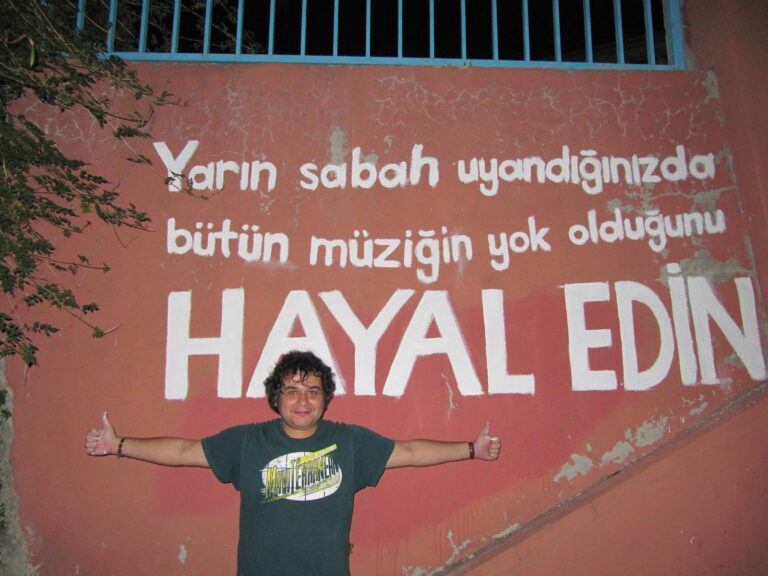

That evening I met with Alp. We had also decided to take a “do it yourself” approach to the “Imagine” graffiti after having been let down the week before by one of Alp’s students. I was somewhat apprehensive about my first encounter with street art in a city whose police are not known for their tolerance, but Alp had found an amazing spot on a set of steps that overlooks the Golden Horn, at the entrance to a busy underpass and next to a small coffee shop whose owners had enthusiastically given us permission to paint on their wall.

Passers-by were curious, and many stopped to talk as the sun set over the old town in front of us. Turkish sentence structures are inverted compared to English and so the phrase begins “Yarın sabah” (“Tomorrow morning”) prompting the question “Yarın sabah ne?”. As the paint slowly spelled out more words the enquiries became more amused and curious, until the command “Hayal Edin” (“Imagine”) finally revealed itself.

It was dark by the time we were finished, but the graffiti looked fantastic, and a frustrating day of doorstepping had reached a satisfying end, and so we went out to dinner to celebrate.

The following morning I went back to the graffiti to take some more photos in the daylight, and to check that the words, unlike the imaginary music, were still there. The rush hour had subsided by the time I got there, so there weren’t as many passers-by as last night, but the words still created a visible impression on many that saw them: A young girl slowed, then stopped, took out her phone and took a picture; a young boy skipped past singing the first line repeatedly “Yarın sabah uyandığınızda, Yarın sabah uyandığınızda”. Others just shook their heads. The photos still didn’t quite manage to do justice to the silhouetted backdrop of the Golden Horn and the old town beyond, but the words are there and the job is done. Just the small job of arranging the recordings and performance of the score left to do then…

So, another day spent walking in the hot September sunshine with my rucksack optimistically heavy with laptop, microphone and printed scores, printed maps and the details of every remaining place of worship I could find (other than Sunni, since we have now arranged to record with Hülya’s mother on Saturday). I had already attacked the a-list of churches, with minimal success, so wasn’t feeling overly optimistic about the b-list today.

Given the ongoing difficulties in finding an Alevi, never mind one willing to participate in an inter-religious project at a time of heightened tensions, I thought I would try instead to snare a Sufi by going to the Galata Mevlevi Lodge. Sufism is a mystical form of Islam which uses music and dance to transcend worldliness (exemplified by the iconic Whirling Dervishes), and so I am hopeful that they will look favourably on this project.

At the gate a helpful man who took more than a polite interest in the project but explained that the site was now primarily a museum, and that no Sufis were there today and that there was nothing he could do for me other than suggest I come back on Sunday at 5pm when they put on a performance for the tourists.

Onwards to the ancient district of Karaköy, where the men sitting selling walnuts and drinking tea amongst the decaying buildings is the only activity in the quiet backstreets. I came here as I had heard that this area was home to a number of Greek and Russian Orthodox churches, but was warned that they would be hard to find. At street level I found a solitary door decorated with Orthodox crosses that was locked, with no bell, buzzer or bystanders (by now a familiar experience).

But looking up, one of the nearby apartment buildings had a dome and cross on its roof, and so I decided to explore. No one was around, so I went through the anonymous door and climbed the six winding flights of marble stairs through the empty building to a top floor landing that housed a large painting of a monastery with a Greek inscription, a set of bells, and a resoundingly locked wooden door with an inset cross. My knocking was heard by no one. Given the magnificent Aya Triada can only attract three or four worshippers to some services it wasn’t surprising that this tiny Church was deserted, but disappointing again nonetheless.

But from the vantage point of the windows on the landing I noticed two more domes tucked away amongst the nearby rooftops and so decided to explore further. It seemed as though the churches all served the small communities housed within the buildings they were perched on top of. I later learn that they did exactly this, and were built as lodging houses for pilgrims passing through Istanbul on their way to the Holy Land.

Back on the street I head through another doorway with a small metal sign with Cyrillic writing on it, and up another six flights of steep wooden stairs, with electric lights that automatically flipped on only after I had ascended each dark flight. I passed only a single old woman scrubbing her doorstep who nodded encouragingly when I asked “Russya Orthodox?” and pointed upstairs into the gloom.

Eventually I reached a heavy wooden door with a small bell at the side, which I rang. Shortly after I heard a shuffling sound from inside and someone fumbling with various latches and locks, before the door opened to reveal a large elderly man, with a long unkempt beard and shabby grey robes secured by a tatty cord. Introducing myself first in Turkish, and then in English, and then in hand gestures, the old man shook his head slowly and said simply “Russya”. Explaining the concept of The17 and enlisting his help would be not be easy, and I couldn’t even make myself understood when asking if there was anyone else there who spoke English or Turkish, and so I beat a retreat.

On the way back down I once again passed the woman still scrubbing her doorstep, and whose half-opened door revealed dozens of Orthodox icons on a wooden dresser. Perhaps she could be my first choir member, but my enquiries of “Türkçe konuşuyor musunuz?” and “Do you speak English?” were again met only with a slowly shaking head and the single word “Russya”.

Back out to the street and to the other domed apartment block I had spied, but this one was securely locked against wandering strangers. Time for lunch instead.

My final destination was somewhere I had been wanting to visit during my time here, but hadn’t yet done so, the magnificent Byzantine Church of St Savior in Chora. Like Aya Sofia it was respectfully converted into a mosque after the conquest of Constantinople (or the fall of Constantinople depending on your perspective), but the mosaics and frescos inside are far more extensive and impressive than those of its better known sibling. But what they both have in common, I discovered, is that they are frequented only by tourists, and no longer used for any form of worship, or have any ecclesiastic staff. Not to be deterred, I sought out English speaking tourists who looked like they might be sympathetic, but weren’t. One elderly Australian women, who was on the trip of a lifetime to Europe and Asia and who had fallen in love with Turkey, initially consented but then backed out and couldn’t be persuaded. Besides, she wasn’t even of any faith, and I suspect my microphone would have picked up the sound of the barrel being scraped.

The following afternoon I headed over to the Asian side to record Hülya’s mother singing the first part of the score. Hülya had already explained about The17 to her mother, but we talked together in broken Turkish about the idea, and she then read “Imagine” followed by “Combine” and I did my best to explain why it was necessary to delete the recording, about the twinned performance in Hackney, and about some of the other activities of The17. After her politely bemused response we got down to the recording. Five minutes had never felt so long to me (or her, I suspect) but finally one piece was safely recorded, and I hoped to (whichever) God that the recorded music wouldn’t have disappeared in the morning.

We then chatted a while, drank Turkish coffee, ate fruit, and talked a bit about our lives and families before I headed off, accompanied by Hülya who was heading the same way as me. On the way we decided to stop off and check out a couple of churches that Hülya knew in Kadıköy. First off was an Armenian Church (Surp Takavor Ermeni Kilisesi) who suggested we go back tomorrow (Sunday) morning when there is a service, followed by the almost obligatory locked door and silent buzzer at the Orthodox Church (Ayia Efimia Ortodoks Kilise) down the road. Back at home I searched the internet for more churches in Kadıköy, and found an English Protestant Church (İngiliz Protestan Kilise), located near the other two I saw with Hülya. Surely my fellow countrymen will help?

So the next day I head back over to Kadıköy to hopefully take advantage of the Sunday morning worshippers. The Orthodox Church is, inevitably, still locked, and the buzzer unresponsive. But at the Armenian Church I manage to explain myself to a man in the courtyard, as people are arriving for the morning service. He helpfully suggests I return at noon, when the Church service will have just finished, and I may be able to find some people willing to participate.

Along the road, the English Protestant Church is not at all what I expected, and certainly doesn’t seem English at all. A small rectangular crumbling white chapel with a corrugated plastic lean-to at the front is providing cover from the sun to a small group of Turkish men. Introducing myself, one of the men steps forward and says that he speaks English, and comes from Hackney! I explain about The17 to him, the “Combine” score and the connection with the Hackney, and with his help start approaching members of the congregation.

We get a few timid expressions of support, and my requests get passed around the hierarchy, and one of the preachers gives the project his blessing, but as more and more people arrive and the in preparation for the 11 o’clock service it became apparent that it would be impossible to make a recording until after the service, and so I was invited to stay. Given that I am asking them to sing for me, it seemed the least I could do was to sing in return.

Being in a strange chapel being preached the gospel in a language I barely understand, and singing hymns with tunes I don’t know from Turkish words projected onto a screen was a highly entertaining experience, for the first hour at least. The packed congregation was a very mixed bunch, and it was hard to determine their ethnic or cultural background – a few white westerners, asians and africans, but overwhelmingly Turkish.

The church had embraced the evangelical use of music (guitars, flute, drums) and the raising of hands, and had also incorporated a section where individual members of the congregation passionately recited a prayer. A video camera captured the sermon for those unable to be there, and it was a joyful, relaxed service with an enthusiastic congregation that I expect would put most English Churches to shame. I declined the communion but was interested to see that loaves of real bread were used, unlike the white wafers I remember from my childhood. As the service went on, and the hymns, prayers and readings continued I realised that I would be far too late to go back to the Armenian Church, and hoped that this sacrifice would pay off.

Eventually the service finished, and I gathered together a few of the younger members of the congregation who had expressed the most interest, including a young lad “Abdullah” who despite his interest in the project was very hesitant as he said he couldn’t sing. I reassured him that this was not important, and we moved to a small hut at the back of the church to make the recording. In between interruptions from people coming to clean the tables, and the collective giggles emitted in response to Abdullah’s best efforts and the ridiculousness of the whole situation we somehow got five minutes recorded. After taking their email addresses, and a photo I went back to the street overjoyed. As I thought, the Albanian Church was again deserted by the time I returned, and the Orthodox Church still resolutely locked, so it was definitely time for lunch.

Back over to the European side, and back to the Sufi Lodge, where the man in the office remembered me, and introduced me to three men out front who were drumming up business for today’s performances. After some initial scepticism they took interest in the project. Whether this was due to the strong affinity Sufism has with music, or whether it was the desperate look on my face I can’t know, but they asked me to return at 6 o’clock, and said they would help.

I spent the intervening time going back to the two Catholic Churches and the Orthodox Church I visited on Thursday and with a similar result. I did however find one group of young men at St Mary Draperies who wanted to participate, and would have done so had it not transpired that they were all Sunni.

Back at the Sufi Lodge I was welcomed at the gates, and asked to wait in the courtyard as the performance was still taking place. I chatted a while with the manager, Ilker, until the Lodge doors opened and the tourists spilled out. Once it had quietened down, and all the souvenir CDs had been sold, Ilker went off to find a couple of Sufi musicians for me, Gökhan and Can. Although they had been instructed to help me, once I explained the concept (as best I could) and showed them the score they seemed genuinely keen to help. Moving inside the Lodge to the serenely decorated hall we settled down and recorded the third note of the score. I know The17 isn’t intended for proper musicians, but hearing their clear voices sing together for the full five minutes in the surroundings of the Lodge came close to a religious experience.

So, after four long and largely fruitless days I was elated to at last have three recordings, but still had no idea where the other two would come from.

We followed up loose ends from previous enquiries, and make fresh appeals. Our Orthodox trail had run cold, but our Jewish friend, Jessica, who had put us in contact with the Rabbi and who had tried herself repeatedly worshippers from her synagogue, finally reaches a “do it yourself”. Although initially reluctant, the more we talk about the idea of The17 the more keen she becomes to participate, although she had already unwittingly become part of the performance through the many conversations she had had trying to recruit on our behalf. But once she understands that The17 does not require musical proficiency (quite the opposite) she is happy to sing. I warned her that five minutes would seem a long time, but when I told her that the time was up she looked surprised and said she would have been happy to sing for much longer, and that she had found it unexpectedly relaxing, almost meditative. As indeed did I.

Our final recording eventually comes through another old friend, Stu, a veteran of the same warehouse parties as me, who puts us in contact with a Turkish Catholic friend of his, Ayla. We meet up, together with her husband Simon, to discuss the project and I do my best to answer their questions, and my own. Simon, despite being a professional musician, said he would love to wake up tomorrow with all music having disappeared, freeing him up with a blank canvas upon which he could create original sounds. We talk together about music old and new, recorded and live and we talk about Istanbul and our lives. New friendships are forged and plans are made to meet up again for the recording.

Ayla later enlists the help of another Catholic friend, Alex, and we meet to record the final part of the score. Singing in church was a formative musical experience for them both, and so the connection in the score between faith and musical expression resonates, as do their voices together. Wonderfully, Alex had by chance seen the graffiti that we had created and, whether or not it now made sense, the ideas rebounded and the recording was complete.

3. Combine

Bringing together the five recordings was an altogether much easier task than bringing together the five groups of singers. The musical arrangement was trivial, just some cleaning and EQing, the arrangements for the performance were far more protracted. Making and changing plans is a Turkish national pastime, and yet despite all the effort that goes into it, the outcome is always far from certain. People dropped out, then back in, whilst others who were in subsequently dropped out or didn’t show. Fortunately the score said only that the group for the performance “can include the members of the five faiths”.

But it didn’t matter. We made arrangements to meet at Hülya s studio (serendipitously at 17:00), and the group that joined Hülya Alp, Hande and me included both of the Catholic singers (Ayla and Alex) along with Ayla’s husband Simon and our friend Stu. Our Jewish friend Jessica joined in via phone, which I hoped didn’t contravene The17’s “no broadcast” rule. Everyone had been involved in the project in one way or another and all were curious to hear the result.

We gathered, we talked, and then we became quiet and listened. As the playback started, it struck me that the music we were hearing was still just a recording being played back on my computer, like any other file. And yet it was also so much more. It was inconceivable that we would skip, jump, rewind or fast forward, and we were all compelled to give it our full attention. We all waited, listened and reflected individually within the group for the full five minutes, and heard the sound of The17.

The music was much more powerful and beautiful than anyone had expected. But the impact it had upon us came as a result of the knowledge of the effort and ideas behind it, the people involved, and the realisation that we were the only people who would ever hear it and would know what it sounded like. The sound from the speakers collided with the information in our heads to create a response much greater than that of the music alone. Had a stranger walked into the room, not in possession of this knowledge, then I am sure this view would have been confirmed.

So, is it is this shared knowledge, and personal involvement that can make the experience of listening to music so much more than that of just hearing a record? And does this go some way to explaining why the medium matters too? Reading about a record in the NME, doing a paper-round, saving money, cycling to town and back, and then excitedly tearing the shrink-wrap and putting it on the turntable can never produce the same impact as hearing a new tune suggested by Spotify on your way to work, or seeing a new YouTube video that has been shared on Facebook. Whilst the clock can’t be turned back (for my generation or the current one) if we are to continue appreciating recorded music, then we cannot just passively consume, we need to contribute something ourselves, even if it is just a few minutes of our wholly undivided attention.

4. Delete

As the effect of the performance slowly passed, and the discussion died down, it became time to delete the recordings. Although it had previously been difficult explaining to people why it was necessary to do this, when it came to it, everyone got it – that shared moment we had together will, and can, never be repeated. The sound of The17 lives on only in our heads, and is all the more powerful for it.

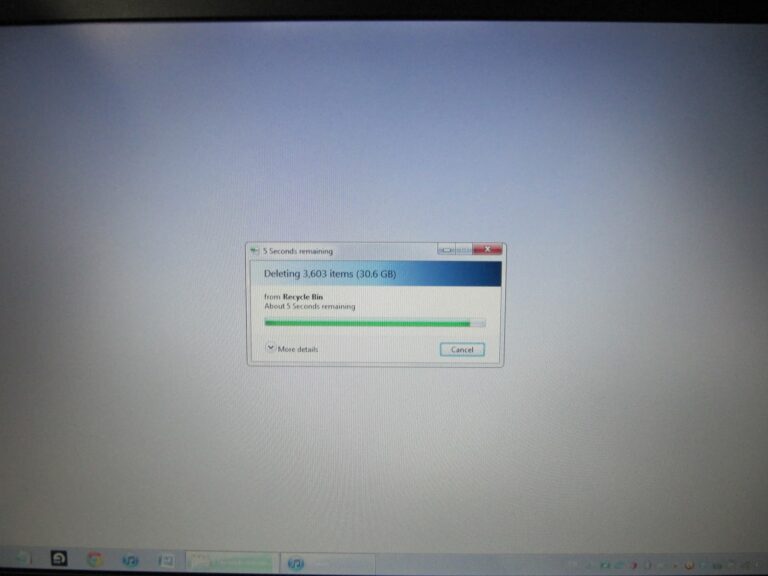

I realised then that I relished the prospect of deleting something I had worked so hard to create, and it appeared that so did everyone else. Everyone crowded around the screen with their cameras, all too aware of the ridiculousness of what we were doing in trying to preserve for posterity a moment of destruction. The files were deleted in an instant, and I then emptied the recycle bin to remove any temptation to recover the lost sounds.

As the sun set over the rooftops, the group slowly dispersed and carried away their memories. The performance was finished. I felt a sense of satisfaction that we had been able to complete the performance, but also a sense of loss, that something was now missing.

But all things pass, and leave you only with memories. Just as my time with The17 was finished, our time in Istanbul was also drawing to a close. As with music, you get out of life what you put in. Taking on this performance, seeing places and sharing experiences with people I wouldn’t otherwise have got to know has been a wonderful parting experience with this remarkable city. We are all now lifetime members of The17, and the ideas and connections that were formed here will continue to echo and combine.

For a map of places referred to please see here.

For more information about The17, for other performances and scores, or to get involved, go to the17.org.